My underground piano concert debut in London ended last month with an encore performance at Stratford International.

By underground I mean Tube and railway stations.

By piano concert I mean I played a selection of pieces on public pianos installed in train station concourses and other locations.

By encore performance I mean Stratford International Station was where I began and ended my . . . tour.

The Stratford was a woody upright, girdled with crime scene tape and chained to a stool. I set up the sheet music for Karl Jenkins’ Benedictus, an elegiac piece from The Armed Man, and made a start. This would be the first time I’d play in front of anyone but I doubted anyone would stop, even to shake their heads in pity. In fact, I counted on it. I’ve practised daily for some time but I’m still a bit shit.

Stratford International was not far from my sister Kate’s place where I was staying so I visited the railway station’s public piano regularly to practise. The first time I played the Stratford, security guards came by at frequent intervals to lift the piano’s top-board and peer inside for bombs.

Back at the Strat next morning I warmed up with Brian Eno’s By This River, a looping, hypnotic, piece. The security guards streamed by one by one, but the Eno got them so opiated with existential ennui they couldn’t remember why they came and regrouped by the electronic gates to gape at commuters.

A supervisor stopped by, shook his head at the cluster and checked inside the piano. He set down the top-board, patted me on the shoulder and said, ‘You’re doing well. Carry on.’

I wasn’t, but I’d passed the bomb test, I hadn’t bombed, or even made a bomb joke to the security guards, so I took his advice and advanced to the Herne Hill railway station piano.

The Herne Hill upright was painted in bright persimmon, heavily graffitied and faced a wall of exposed brick. A sign said, ‘Thanks for keeping the piano playing’, but it could only be played Thursdays and Sundays when the keyboard was unclamped.

I took a run at Benedictus, then switched scores to play an instrumental arrangement of Thom Yorke’s Dawn Chorus. At the top, Yorke’s stage directions read, ‘Play as if it was too late, but the sky’s still beautiful. The repeated chords — G7, Em7/G, D, Dsus4, G/B, Bm, Dadd9, act as a kind of pulse, borderline dissonant at times, and at one point seem to create a choral harmonic that floats above the piano.

The work is all heart. You can take liberties and punk up the tempo and even mistakes can sound deliberate.

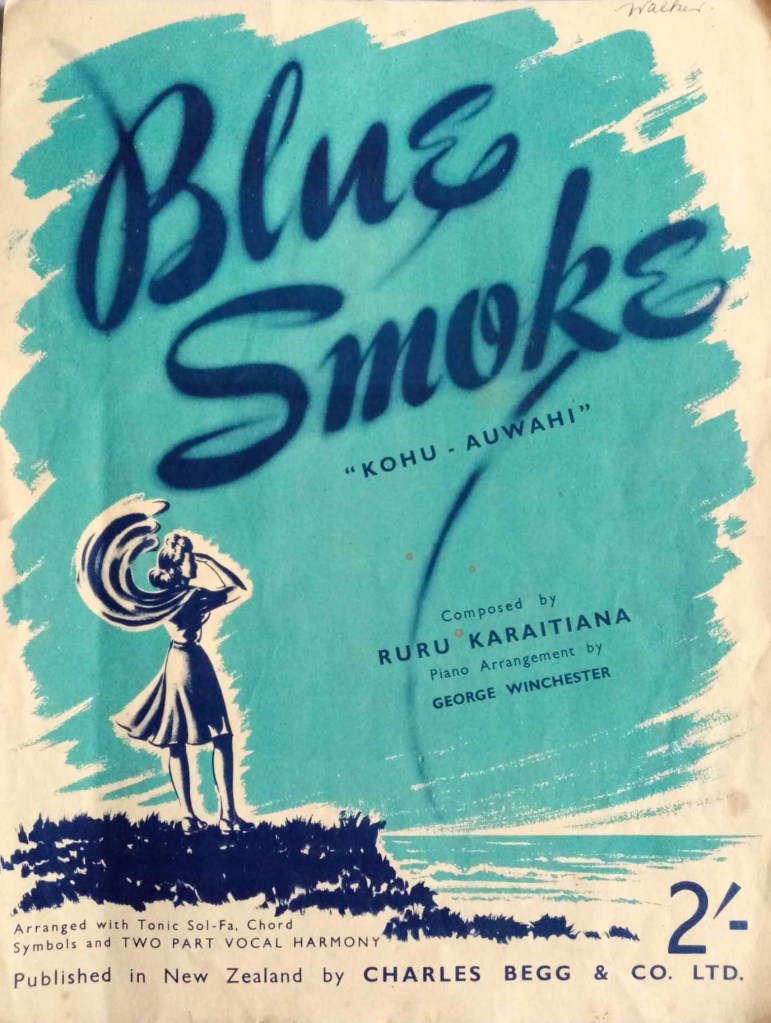

The piano sang with a warm buzzy resonance I thought would suit Ruru Karaitiana’s Blue Smoke, a wistful song of longing. The jazzy chords were a challenge; I played the piece clunkily — more so when a tall black bloke and a short white bloke stood nearby and talked loudly. They edged closer.

I asked the tall bloke if he was waiting for a turn on the piano. He seemed bemused to have been asked. He was local; I was a day tripper, and I hadn’t even left the station. I stumbled off the platform and dropped my satchel. Sheet music spilled out.

The tall bloke sat down at the keys. His mate said, ‘We were just saying, we’ve never seen anyone with sheet music here before.’

‘There’s a first time for everything,’ said the tall bloke, and played his mix of blues, gospel and soul, sans sheet music, at cathedral-grade volume.

I scooped the scores back into my satchel. The chatty bloke said I’d find other public pianos at the St Giles cancer hospital, where he worked on Wednesdays, and that there was another piano at St Thomas Hospital, and that at both hospitals patients loved to hear anyone of any ability play at any time. Oh, and there was a piano at London Bridge—no, yes, there’s a pipe organ there but there’s a piano too—it’s around the corner.

I listed his pianos on the back of my hand and caught the train out of there.

Next on the itinerary, though, was the shiny, black Yamaha digital piano in the Barbican library.

The Barbican is a Brutalist, labyrinthian, anti-tactile arts institute and residential stone fortress. It’s near Moorgate, formerly a northern gate in the city’s defensive wall, and named after Moorfields, the marsh outside the wall. The site was a good fit for the raw concrete giant whose name comes from the Latin, Barbecana, a fortified outpost.

The Yamaha was the Barbecana’s beating heart; it could be reserved for an hour at a time and played with headphones. I booked a time, found the library, put on the headphones and played Erik Satie’s Gnossiene #1, but in tree-falling-in-a-forest-with-no-one-to-hear silence. I had another go at the Benedictus, and a simplified version of Adagio in G Minor by Remo Giazotto but wrongly attributed to Tomaso Albinoni.

Near the end of my allotted time an old bloke stood by to wait for his turn. I gave myself five minutes to pack up before the bell but sensed the geezer’s impatience. He waved away the headphones, he’d brought his own. He sat down and played vigorously in silence. When I looked back his face was lit up with joy.

The Barbican library Yamaha couldn’t really be counted as a railway station piano so next morning I headed for London Bridge. The station’s pipe organ would be well suited for the offertory from French composer Charles Gounod’s St Cecilia Mass.

St Cecilia is the patron saint of music. The offertory is an interlude played while the offering plate is passed around during a church service. Gounod’s Offertory is a floaty, rising and falling piece that sounds like waves of sighs—but the London Bridge Station pipe organ’s keyboard was short, I didn’t know how to use the foot pedals or the stops so couldn’t get the reverb effect I’d got used to on my Kawai digital. My performance of the Gounod’s Offertory sounded more pop-goes-the-weasel than soft pine tree sough.

A search for the London Bridge piano the Herne Hill chattyman had mentioned also came to nothing. The security guards shook their heads, they’d had never seen one.

I crossed the road to Guy’s Hospital and asked at the front desk about their piano but I already knew what the answer would be.

In need of a win I returned the following day to the Stratford. I had a crack at a simplified version of Schubert’s Standchen, then played the melodramatic The Prisoner Comes, from Gilbert & Sullivan’s comic opera, Yeoman of the Guard, to accompany commuters heading for work.

A bloke in a beige cardie stopped by.

‘How’s the piano?’ he said.

‘Good,’ I said, ‘but a couple of the top notes are out of tune. Maybe they’ve always been out of tune but I only noticed this morning.’

He said he was a pianist and composer. ‘I’ve just finished a tour with an orchestra. It went very well. A friend said he’d film me if I liked,’ he said. ‘I said how do you do that? It’s a dark art to me. Now, I reply to all comments on my webpage but after he posted the footage I got more than 10,000 comments. No way can I reply to all of those.

‘Could I have a go?’

‘By all means,’ I said.

He began to play. It was a lovely piece with seasonal changes in tempo and mood. It was his own composition, he said. He introduced himself as Duncan Moss. Said he was on Spotify and had a website.

I googled him later. He’s self-described as a visionary pianist and composer, known for his rich, evocative instrumental compositions. He’s played piano since he was six years old, has sung in church choirs , cathedral choirs and the London Symphony Chorus and in various bands. After 30 years in business he was diagnosed with a health condition. ‘So I worked out what was important and jettisoned everything and reverted to music full time.’

‘My wife and I were waiting for our train to Cambridge,’ he said. ‘I said I can hear a piano and came over for a look. How long have you been learning piano?’

‘About a year,’ I said.

It’s been much longer than that but I’m still a bit shit.

Then his wife came to collect him.

‘You’re doing well,’ he said. ‘Keep it up.’

I had another go at Blue Smoke. A bloke with a small dog in his arms passed by and muttered ‘terrible music’.

I might have misheard, but it was about this time I realised I wasn’t practised enough to call this tour a concert. I wasn’t ready. The titles on my playlist sound grand, but they’re mostly ambient works with a tempo slow enough for me to handel. The selection wasn’t entirely, as someone kindly put it, a ‘stylistic choice’. I decided to make Benedictus my hero piece and aimed to play it perfectly at least once before I flew out.

And so, with renewed purpose I headed for Liverpool Street the following morning.

The bright blue upright decorated with a white line drawing of a tropical plant stood at the centre of Devonshire Place, a Liverpool Street business precinct. To the left was a broad courtyard ringed by a florists shop and offices. To the right was a restaurant with tables set up outside. I got there early enough to avoid the lunchtime crowd.

I played Benedictus several times but fat fingered the chorus so had a go at the theme music from the movie Love Story. Possibly a poor choice because I was halfway in when a passer-by interrupted me to say, ‘Excuse me, sir, do you know where I can get a massage around here?’

Was it the vigour of my fingering that stirred his blood? Was he expecting my performance to come with a happy ending? And, if so, how much should I charge?

I was discombobulated, I jotted down some notes, fat fingered the Benedictus again, gave up and went home.

So making the St. Pancras International Railway Station’s public pianos my next stop might have been an over-reach.

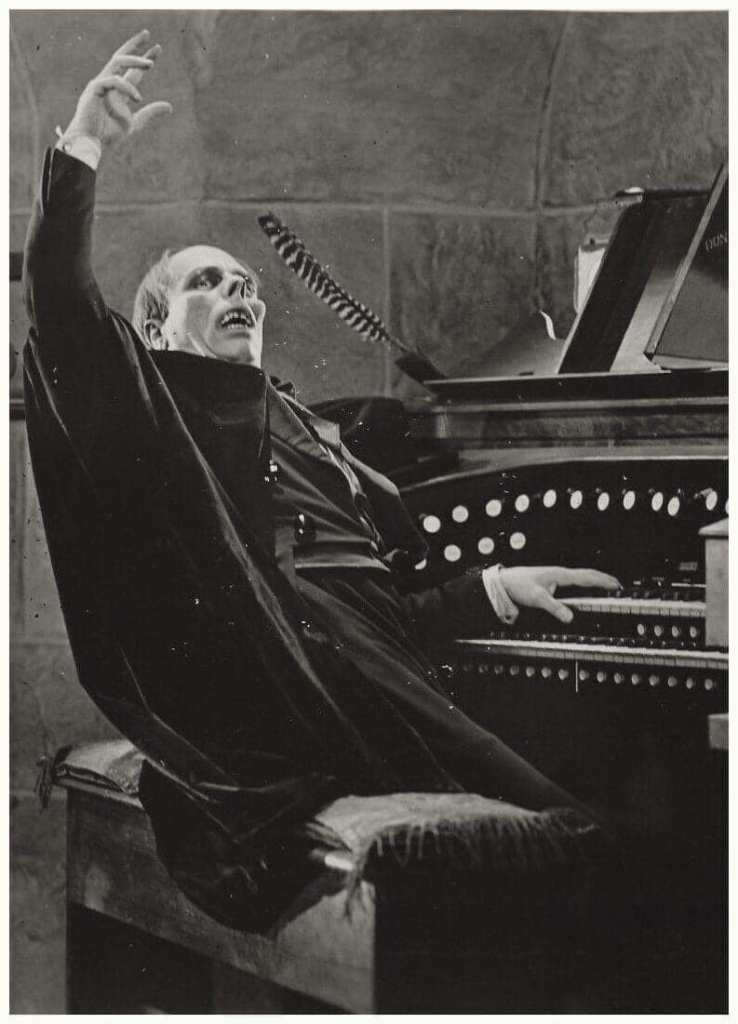

The Phantom Piano was a shiny black Yamaha adorned with a decal of the white half-mask worn by Erik in Phantom of the Opera. It had been donated to St. Pancras by Andrew Lloyd Webber Musicals and musicians such as Elton John, Alicia Keyes, John Legend, Jools Holland, Jeff Goldblum and Lang Lang had performed on it.

When I arrived an exuberant pianist was playing a jacked up, jazzy version of the theme music from the movie The Pink Panther. A woman filmed him on her cellphone through several takes. A crowd formed as other people stopped to film him on their phones too.

I wandered up the arcade to the other piano, a black Kawai-500 upright set behind a glass elevator shaft.

A thin man in a suit with a briefcase at his feet played a complicated piece. The cover of the score in front of him read Liszt. He was playing Liszt without even having to look at the music. I loitered for a bit then returned to the the Phantom Piano. The jazz pianist and camerawoman had gone. I sat down and set the score for Benedictus on the music rack. An East European woman in a headscarf and coat stopped by and peered at the title. Her face lit up, she said something in her own language. She might have been a conductor or composer or famous Romanian pianist, I’ll never know. She gave me a thumbs up and said, ‘Success!’ I hadn’t started playing yet so she might have just been wishing me luck.

I played the opening notes but two keys were mute. This hadn’t been an issue for the jitterbugging Pink Panther pianist but Benedictus is an elegiac invocation. The chorus is climactic but with two missing bass notes it would sound like a potato. I gave Dawn Chorus a go but it came out all wrong. I packed up and went back to the Kawai. The businessman was putting the Liszt score he didn’t need to look at back into his briefcase. As soon as he was gone I slid onto the piano stool and played Dawn Chorus, then Benedictus.

A teenager stood nearby, waiting for a turn on the piano. He asked what I had been playing. I told him it Benedictus from Karl Jenkins’ work The Armed Man, a secular, literary, modern mass to peace made up of 13 songs that arced through the experience of war, from horror to hope, but his attention had faded at Benedictus.

He sat at the piano and played a bouncy, happy, simple and complex tune. He said the piece was called merry CD and was from the video game Omori.

Omori is a role-playing video game in which the player controls a hikikomori (reclusive) teenage boy named Sunny and his dream-world alter-ego Omori. The player explores the real world and Sunny’s surreal dream world as Omori, either overcoming or suppressing his fears.

Waterloo Railway Station, my next venue, was more Harry Potter than it was Omori.

A bookseller’s directions to the station’s public piano led me up a staircase in the station’s hinterland and to an exit onto the street. A security guard told me to take another set of stairs, turn right at the end of Platform 19 then head downstairs. And there it was, at the centre of circle in the middle of an almost deserted, subterranean concourse, a Young Chang upright, laminated with a rose and blue wrap inscribed with sponsors names and the tag-line, ‛Let’s make music.’

The Young Chang looked most promising except several keys were dumb as stones and the mid-range F was flat.

Nothing to be done. Except head to Battersea Power Station and try my luck with the public piano there.

Once home to two power stations, the brick monolith is now an industrial chic, multi-levelled retail and recreation complex. The People’s Piano was tucked under the platform of a broad, concrete stairway in Turbine Hall B.

The hall was a remote, dimly lit part of the building so Eno’s By This River was a good fit to warm up with. Dawn Chorus followed then several runs at Benedictus.

Few people were about but some jokester called out, ‛Give us a tune.’

‛You hum it son, I’ll play it,’ said someone else, riffing on the old PG Tips TV ad.

I stopped playing, wrote the witticisms down in my notebook and looked up. Kate and her friend Andy grinned down from the landing.

Kate had taken pictures of me playing Benedictus. Seated at the upright in the expansive turbine hall, I made a diminutive figure — like cartoonist Leunig’s solitary traveller Vasco Pyjama, she reckoned.

The Stratford was still wrapped in its yellow tape, still chained to its stool like a prisoner granted parole, when I returned to the international railway station the next day for my last . . . performance. I was clunking through Blue Smoke when a young mum and her boy in a pushchair stopped by. I asked if she was waiting for a turn. She said no, her son just likes music.

‛He’s come to the wrong place,’ I said.

She laughed. ‛He’s not that harsh a critic.’

After they left I propped up the score for Benedictus, my final piece, and played it a couple of times to try and nail that perfect rendition.

An affable bloke in a tropical shirt stopped by.

‛That was good,’ he said. He said he’d come across a piano performance of Benedictus on Spotify then later found a choral production of it on YouTube.

‛It’s my favourite piece,’ he said. ‘I know you’re only practising—but I like how you played it.’

And so, the closing notes of my last run at Benedictus for my 2025 underground London concert tour ended in D.

For disappointed. For I never achieved a flawless execution of Benedictus. My London underground piano concert tour had been more about practise than performance, more about the story than the notes. Wherefore the sense of achievement, the joy of ticking off an item on the bucket liszt?

I don’t want the closing notes of this story to B♭ so I asked Ai for a better ending (high five, Omori!) She went beyond the call of duty and hallucinated a high sugar-content coda from a parallel universe.

I went back to Stratford to finish where I’d started. The piano was still wrapped in its yellow tape, still chained to its stool like a prisoner granted parole. I set the Benedictus on the stand and began to play. Duncan Moss passed by on his way to a train, paused, and said, ‘You got it. Don’t overthink it.’ He filmed a minute on his phone; later he sent the clip with the message, ‘Keep doing this. The world needs unprofitable beauty.’

A nurse who’d been on her break came over and told me a patient in St Giles had asked for Benedictus once, because it reminded him of a choir at a church he and his wife used to go to. ‘He doesn’t speak much now,’ she said. ‘But when he hears it he smiles.’

I didn’t play perfectly—but for the first time the mistakes felt like marks on the map rather than holes in the story. I finished, and a few people clapped. A little boy said loudly, ‘Again!’ and everyone laughed. I packed up, closed the fall board and walked away like someone who’d left something where it belonged.